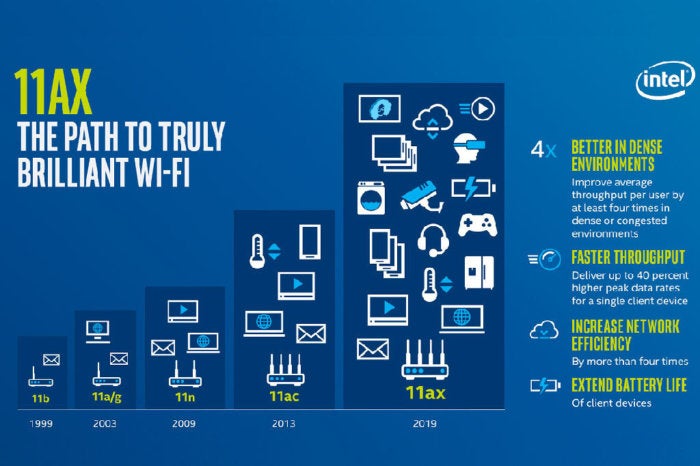

With 802.11ax, the IEEE engineering group that drives standards like wireless local area networking (WLAN) has pushed hard in several directions to make these complicated environments work. There are a lot of benefits for dense corporate networks that need massive throughput and could have tens of thousands of roaming and fixed Wi-Fi clients, but there’s no shortage of upsides for home users or small offices, especially when it comes to video streaming and file transfers.

Intel

Intel

Several techniques in 802.11ax will reduce the effects of interference and increase throughput in crowded urban and suburban environments, reducing typical frustrations that are hard to troubleshoot or fix.

The standard hasn’t been completed yet, but manufacturers are jumping the gun as they have with every new flavor of Wi-Fi for more 15 years. As a result, some equipment could be on the market as early as June, and more is coming later in the year. But the advantages of being an early adopter might pale in favor of waiting for a fully baked version that’s stable and is supported by the client adapters onboard phones, laptops, and other gear.

How 802.11ax makes gains

To explain the advantages of 802.11ax, we must drill down briefly to review how Wi-Fi works. The airwaves are regulated nearly everywhere in the world, and in the U.S. and in most countries, two chunks of frequencies are allotted to uses compatible with Wi-Fi: the 2.4 gigahertz (GHz) band and the 5GHz band. These bands are further divided into channels that have a set starting and ending frequency.Senders and receivers, like a Wi-Fi router and laptop, agree to use the same channel to communicate back and forth, and dozens (or even hundreds) of devices can use the same channel at the same time to relay data via an access point. In cities and suburbs, dozens to hundreds of networks might also be contending for the same channel in relatively close proximity.

D-Link

D-Link

Here’s a top-level rundown of how 802.11ax pulls this off:

Denser data encoding

Wi-Fi encodes data into radio waves, and there are calculable limits to how much data can be carried at a given frequency. WLAN standards, however, are still working toward that upper maximum. Over time, the chips that process signals have become more powerful, allowing more efficient cramming of data into the same space, especially over very short distances between a base station and a receiving device, typically in the same room and with line of sight, which is perfect for video streaming. National Instruments

National Instruments

Adding 2.4GHz back into the mix

The 2.4GHz band is often given shorter shrift, because it’s crowded full of other so-called unlicensed uses that rely on wireless data—like baby monitors, wireless doorbells, cordless phones, and the like—that don’t play well with high-speed Wi-Fi networks. Many of those non-Wi-Fi uses have shifted to other bands or now rely on Wi-Fi. 802.11ax is the first standard in more than a decade that improves performance in 2.4GHz, which opens up as many as gigabits per second more data while also taking advantage of that band’s long wavelengths compared to 5GHz: longer wavelengths better penetrate solids objects, like walls, floors, and furniture.This is especially useful for mesh networks, in which current mesh nodes typically have two radios, one for 2.4GHz and one for 5GHz, one of which is used to communicate among nodes. With much higher data rates on the better-penetrating 2.4GHz band, mesh networking with 802.11ax will result in better throughput across a whole network.

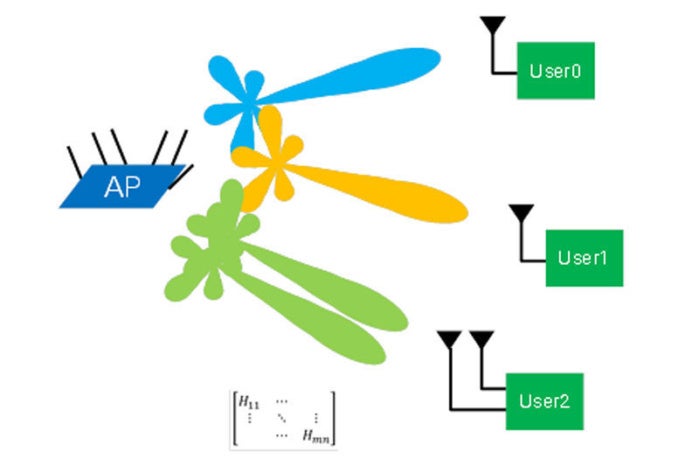

Talking and listening to multiple devices at once

The 802.11n standard added a spatial multiplexing technology known as MIMO (multiple in, multiple out). MIMO is a means of sending multiple streams of data across different physical paths, like playing billiards with radio waves. This required multiple sending and receiving antennas and the equivalent of additional radios for each stream. But many devices, especially small mobile and smart-home units, didn’t have multiple radios. A wireless router with MIMO thus wastes much of its potential bandwidth at any given time when it’s constrained to a single stream. National Instruments

National Instruments

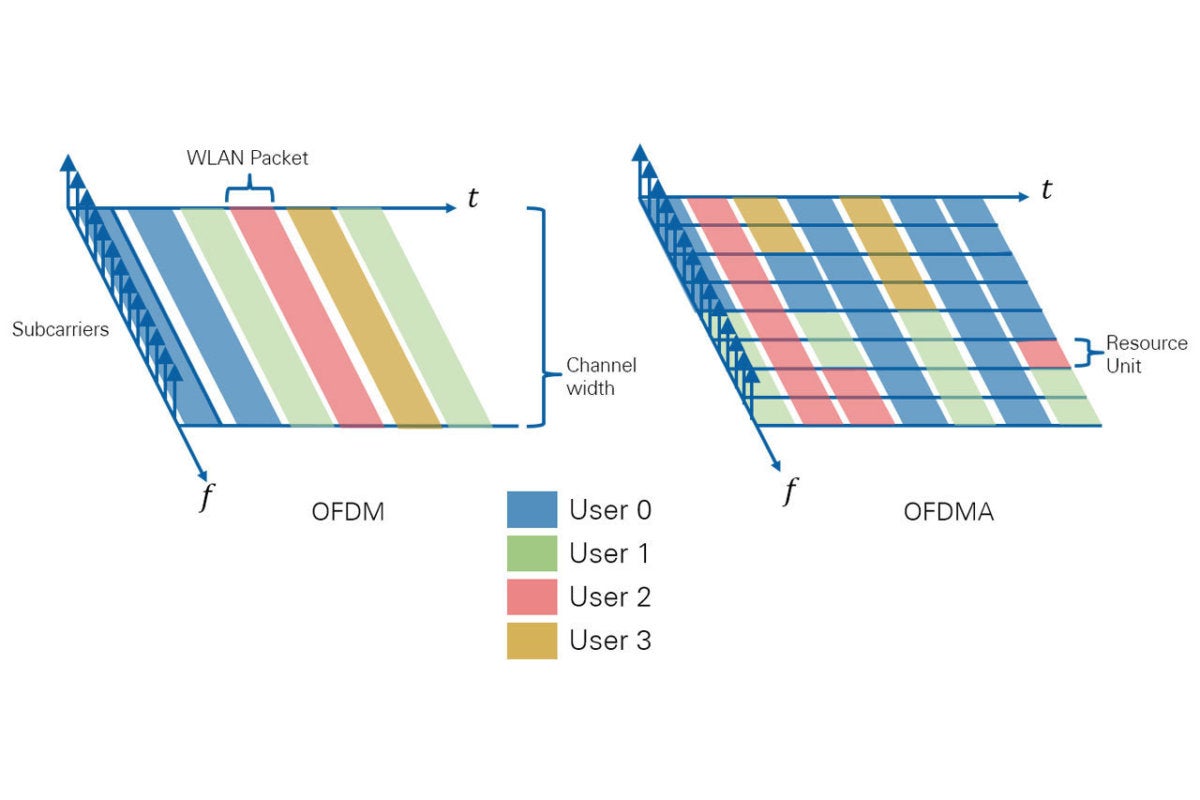

Subchannels

Borrowing a trick from 4G LTE and a few earlier standards, 802.11ax adds a way to break a Wi-Fi channel down into as many as a couple thousand tightly spaced “subcarriers” or subchannels. Each of these subchannels can carry various combined payloads of data for different devices, and interference or noise in one subchannel is isolated from the rest, reducing the need to retransmit or slow down the entire conversation to a lower data rate that can be received clearly. (This tech is called Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access or OFDMA.) Qualcomm

Qualcomm

Qualcomm

Qualcomm

Better discrimination of other networks

In many cities and suburbs, dozens to hundreds of Wi-Fi networks overlap. 802.11ax includes a technique that will let the standard discriminate between the network you’re on and weakly received signals from other networks, which in turn allows greater throughput.A host of smaller technical improvements

While the elements above might seem technical enough, a number of other small improvements add up, including letting 802.11ax break up data for a single destination into different sized chunks to fit into available slots, using longer runs of encoded data, and better focusing energy for “beamforming” to target receiving devices more exactly. 802.11ax is also better at avoiding conflicts where devices talk over one another, called contention.Improved client battery performance

Here’s one more bonus that’s not related to speed: Various mobile-targeted improvements, including one that tells network client devices that put their Wi-Fi radios to sleep to conserve power when exactly to wake them up. This could dramatically reduce Wi-Fi-related power consumption, extending battery life.The risks for early adopters

While the standard is still under development at the IEEE task group, some manufacturers are prepping for the near-term release of Wi-Fi routers that will be labeled 802.11ax, even though they’re using a preliminary version of the spec as interpreted by a single manufacturer or chipmaker. D-Link and Asus announced routers at CES in January, and as chipmakers get close to finalizing 802.11ax chipsets, we’ll see more manufacturers start to make their plans. Asus

Asus

Manufacturers and chipmakers sit on the IEEE committee making decisions and are part of the Wi-Fi Alliance that certifies products as interoperable, but it’s still a risk.

Few of 802.11ax’s advantages can accrue without new client adapters in phones, tablets, computers, and other devices, and those always come more slowly as new generations of equipment are introduced. While 2019 will likely be the year that 802.11ax starts to appear in hundreds of millions of new devices, it will still easily be two or three years before you have enough new equipment to take full advantage of the new technology.

Backward compatibility is always a concern for new generations of hardware, but the history of Wi-Fi has largely encompassed all previous standards without too much compromise. Routers that declare themselves as supporting 802.11ax will also seamlessly handle every previous 802.11 standard, typically back to 802.11g, the first version to support more modern network security methods. With few exceptions, you can keep using all the devices you used in the past.

You won’t need to configure anything special to enable backwards compatibility, although some routers may have modes you can turn on that disable older forms of Wi-Fi. Compatibility comes with an overhead cost, and turning off older modes can boost performance somewhat.